June 22, 2019

Back from NarraScope 2019

Mark and I have recently returned from NarraScope 2019 AKA NarraScope #1. It was held on the MIT campus in the Stata Building. MIT is very nearly a holy site for physicists, so Mark and I were both excited. Plus, I hadn’t been to the northeast before.

On the first day of the conference (Friday), we went to a talk that showed us how to use Inform7, the standard tool for creating parser-based interactive narratives. One interesting thing about it is that is uses natural language. You type “Your Filthy Hovel is a room.” and then it makes a room called ‘Your Filthy Hovel’. Assuming I teach Interactive Storytelling again at St. Edward’s University, I will be making an Inform7 assignment. The class was taught by Anastasia Salter, professor of Digital Media from the University of Central Florida, and Judith Pintar professor of Sociology at Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Mark and I had dinner and drinks with faculty and graduate students from UCF that night and I learned just how enormous their program is. They have game classes the size of the size of the entire VGAM department at St. Edward’s.

Mark’s lightning talk about multiplayer interactive fiction was in the afternoon on Saturday, so we had the morning to enjoy other talks. We decided to divide and conquer. First we went to the Keynote speech. It was by Natalia Martinsson (Killmonday Games), the artist and designer behind Fran Bow, and it dealt with applying emotional intelligence to games, their development, and running a game company. I haven’t played Fran Bow but I plan to remedy that and to get their upcoming game, Little Misfortune.

Immediately afterward, I went to a talk by Aaron Zemach, who gave me a great new lens through which to examine game narrative. He also gave me a vocabulary word for a concept I have been thinking about for a long time: ludonarrative dissonance. That term was coined by Clint Hocking in 2007, and it refers to a conflict between a video game’s narrative as told through the story and the narrative as told through the gameplay.

Aaron’s talk discussed the role that playwriting and improv could play in understanding and creating narrative games. He laid out all plays as a series of actions. Each action has two parts: the trigger and the heap. A play proceeds from an initial disruption of the status quo (stasis), which causes the first trigger. That trigger has a heap (result). The next action is taken as a response, and it has a result. This chain follows until a new stasis is achieved at the end of the play. The example given was that of Romeo and Juliet. In the play, the Capulets and Montagues have been in conflict for a long time. This is changed when Romeo and Juliet meet. And a new stasis is achieved when they die and the feud ends.

The part I found particularly meaningful is how Thought, Character, and the Morality of the story are demonstrated through actions and nothing else. Thought is shown by the trigger one chooses in response to a previous heap. Character is the sum of all one’s actions, and the story’s Morality is shown in which kinds of actions are punished or rewarded in the play. This last part is especially meaningful for games. As Cat Manning pointed out in a subsequent talk, Middle Earth: Shadow of Mordor was developed with this great engine for procedurally building intelligent orc enemies. Unfortunately, to appreciate much of the depth of this engine, you had to enslave orcs. Then the game treated you like a bad guy. Talk about ludonarrative dissonance! According to Cat, the ultimate moral of this game is, “Slavery is … bad?”

Meanwhile, Mark attended a panel discussion on Bandersnatch (which falls nicely into the category of interactive fiction). The panel included Emily Short (Galatea, Spirit AI), Mary Duffy (Choice of Games), Jason Stevan Hill (Choice of Games), and Ian Thomas (Talespinners). Stay tuned for an upcoming blog post by Mark detailing his own thoughts on Bandersnatch. Mark then attended a talk called “How Telltale Designed Tools for Efficient Narrative Development” (a topic near and dear to him) given by two former employees of Telltale Games.

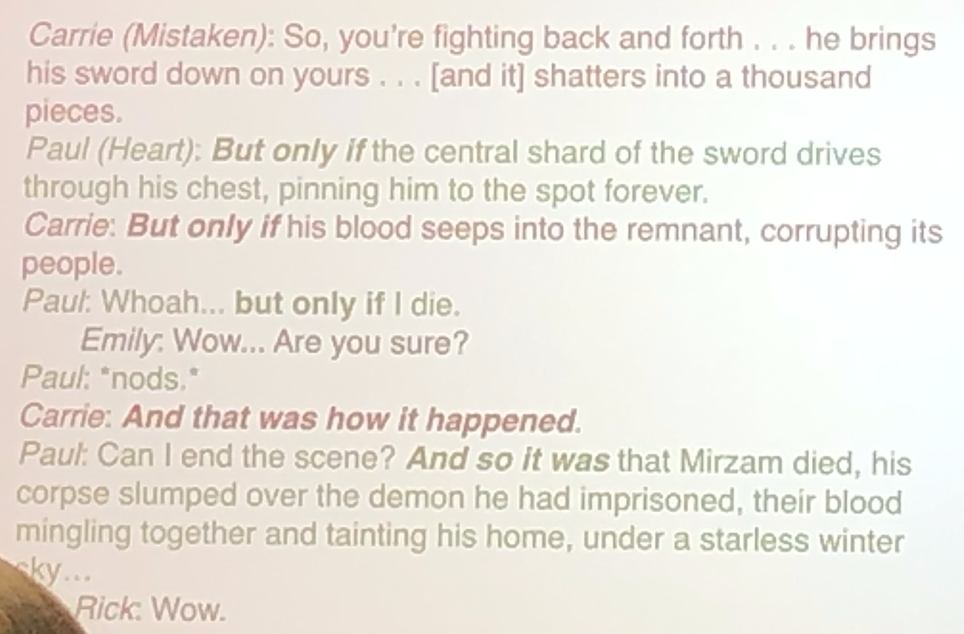

Later, Mark and I both attended a talk titled “What Digital Storygames Can Learn from Analog Storygames” by Aaron Reed. The talk was just incredible. I was so impressed with one game in particular, Polaris: Chivalric Tragedy at Utmost North. It’s a storytelling game with some mechanics and rules, which provide content, rules for negotiating the story, and a guarantee that it will turn into a tragedy. The story is, in part, crafted by a back-and-forth exchange between a tragic hero (Heart) and a demon (Mistaken). The veto phrase, “It shall not come to pass,” ends a conflict in a kind of failure to negotiate a story conclusion. The words, “And that was how it happened,” cement the negotiations into a story. You can end up with quite dramatic exchanges like one shown in the talk.

There were also a few lightning talks that day that were great. I especially appreciated one by Ian Michael Waddell encouraging failure in games. If you make a failure spectacular enough, players may become interested in replaying to intentionally fail.

Mark gave his lightning talk about multiplayer interactive fiction. It included a couple of things that we have never shown before, including an equation which we derived to talk about how out-of-control the needs for content creation can get. An equation is mandatory in all talks given by a physicist, so he didn’t disappoint. His talk was live tweeted by none other than Emily Short, a principal figure in interactive storytelling. We’ll be posting more about that talk here in the future.

That rounded out the first full day of Narrascope. We joined a mixed group for dinner and drinks and then took a long walk to buy ice cream. It was one of the most eye-opening days in terms of just how many narrative angles exist that I haven’t thought about, despite that I’ve been thinking about this nearly nonstop for years, maybe my entire life.

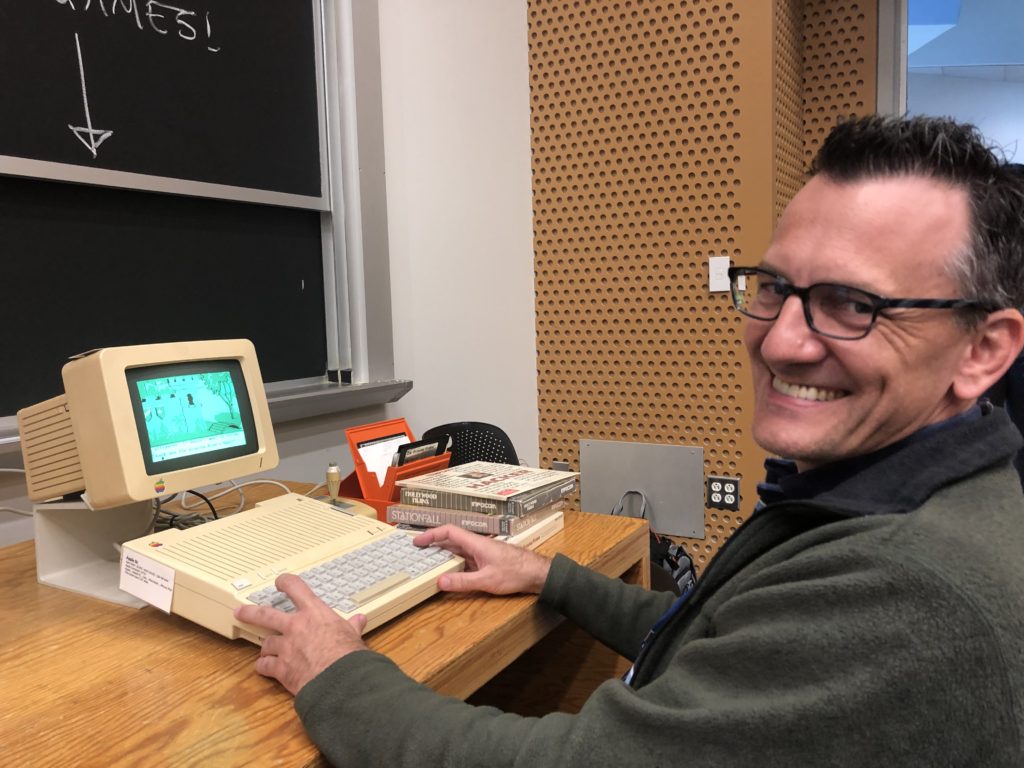

The last day was a little more low-key. We had our game up briefly in the demo room. We didn’t demo it very long, because the real buzz around it was the multiplayer aspect, and currently we only have a demo with the single-player prologue. There were cool things in the demo room, though. There was a Commodore 64 and an Apple 2c running various games. Mark lasted almost 2 seconds playing King’s Quest before he fell into a moat and drowned. I was shocked that there were so many 5.25 inch floppy disks still in perfect working order. I remember the lifespan of any 3.5 inch floppy I owned was only a few months. Trying to install a game from a stack of 12 of them always turned into a tragedy when one turned out to be trash.

That afternoon I went to a couple of panel discussions. I learned about the monetization of interactive fiction particularly in romance visual novels. One strategy is to hide the especially desirable choices behind paywalls. It sounds like it might be both effective and obnoxious.

I went to another panel discussion about procedural generation in games. It was moderated by Chris Martens, and featured Stephen Ware, Stacey Mason, and Aaron Reed. As we all know, the best part of any procedural generation is a hilarious fail. Aaron is working on the Spirit AI character engine, and he talked about a wanting to procedurally elicit a greeting from an AI character in response to a greeting given by a player. AI characters were given a drive toward politeness. An early bug appeared when a player would say hello the generated character would say, “Hello. Hi. Hello. How are you? Hello…” infinitely. What’s more polite than responding politely? Responding politely an infinite number of times!

Stacey talked about experiences where a player would murder an AI-driven character’s best friend, and that would result in the AI character very mildly breaking up with the player. This was because the code looked for the place where the character had lost the most relationship with the character, and used that as an excuse. Stephen talked about a case where, in a game, a procedurally-controlled guard would get hungry. Since the guard had no money, he would steal food. But since he’s a guard, he would then attack himself.

Meanwhile, Mark attended two talks: “Engineering Empathy” by Dave Gilbert (Wadjet Eye Games) and “Making Horror: Hacking the Brain in Games” by Ian Thomas (Talespinners).

There were other talks. Too many good ones for one person or even two people to attend. It was likely the best-run conference I’ve been to. There was plenty of food at all times, no speakers ran over time, there was just the right amount of mingling and discussion, and most of the important people were there. I hope we have a multiplayer demo of our game ready for the next conference, and I hope Mark and I both get to go to NarraScope2020.